- Opinions vary as to whether an attorney should or should not go in-house.

- Some attorneys believe going in-house was the best decision of their career, while others strongly disagree.

- This is why going in-house is the most important move one can make in their legal career.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to provide you with insight as to whether or not you should go in-house. Many attorneys claim that going in-house was their best career move. Conversely, some attorneys claim it was their biggest career mistake. In the end, going in-house is entirely up to you. You need to understand, however, that the decision to go in-house is one of the most significant career decisions you will ever make as an attorney.

|

| Harrison Barnes |

In this article, you will learn what it means to be an in-house counsel, the major drawbacks of being one and what moving from a big law firm to an in-house position tends to do to your future career options.

What does going in-house mean? As an attorney, your options for practicing law usually fall into three categories: working for a law firm, working for yourself (solo practitioner), or working for a company. When you work for a company whose main business is anything other than practicing law, you are an in-house attorney. With that in mind, you may be wondering what does an in-house legal team do? The matters an in-house legal team handles vary depending on the business the company engages in. An in-house legal team may deal with corporate and tax law, mergers and acquisitions, financing and fundraising, patents and other intellectual property, real estate, healthcare, and other practice areas. At a smaller company, there may be one or two in-house attorneys who handle matters in various practice areas, while larger companies often have legal teams with each attorney focused on a single practice area.

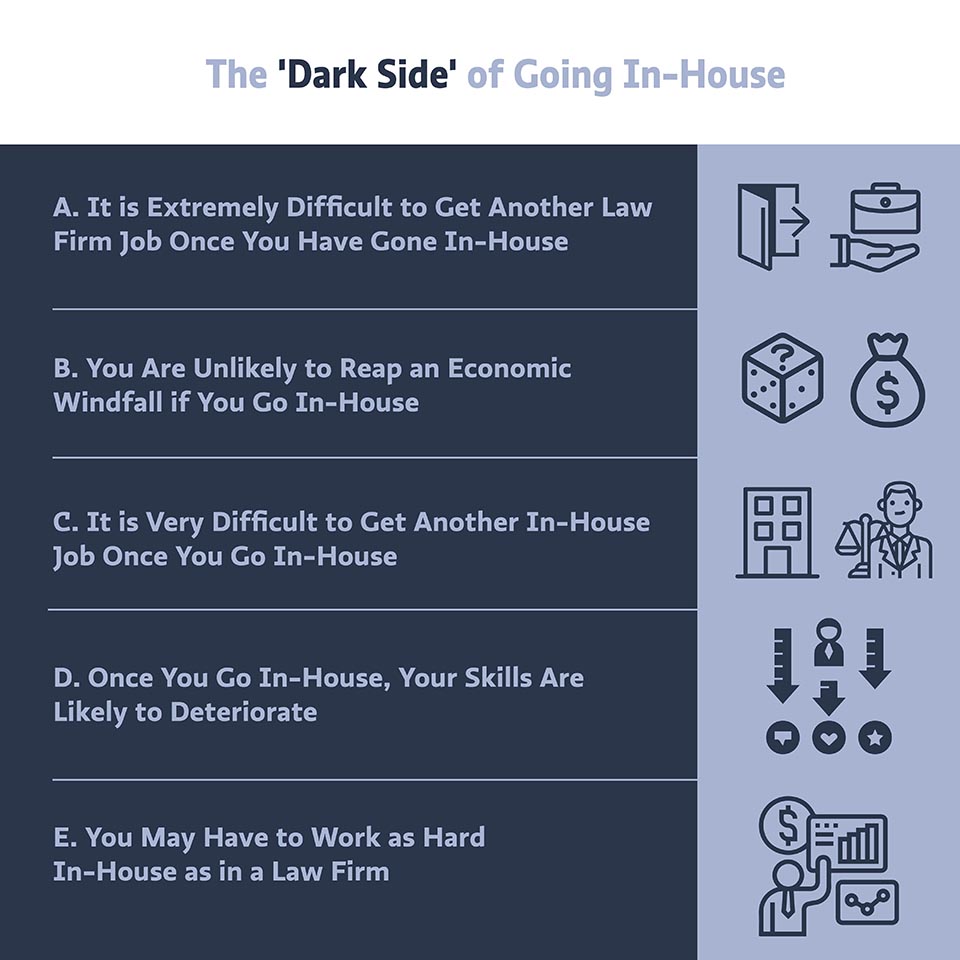

Are in-house lawyers happier? On the plus side, many attorneys go in-house for more interesting work, shorter hours, potentially lucrative stock options, and the opportunity to be on the business side in a corporate environment. Depending upon the environment, these reasons for going in-house may be entirely justified in all respects, and you may find yourself in an ideal situation. Yet, there are several little-known facts about going in-house that may not necessarily make it the best career decision for you:

- It is extremely difficult to get another law firm job once you have gone in-house;

- The overwhelming majority of attorneys do not reap an economic windfall when they go in-house;

- It is very difficult to move to another in-house job once you have gone in-house;

- Your legal skills are likely to deteriorate once you go in-house; and

- You may have to work as hard in-house as you did in a law firm.

![]()

A. It is Extremely Difficult to Get Another Law Firm Job Once You Have Gone In-House

A significant portion of the attorneys contacting us are those whose most recent experience is in an in-house legal department. We rarely are able to help these attorneys transition into a law firm because law firms simply do not want them, regardless of how good of a law school they went to or how stellar their last law firm was. The market tells the story: Once you go in-house, you had better understand that you will be very unlikely to ever practice law with a large law firm ever again.

- See Why Going In-house is Often the Worst Decision a Good Attorney Can Ever Make for more information.

During the late 1990s and the first part of 2000, thousands of attorneys left the law firm world and went in-house at a rate that is unrivaled by any other time in history. In major markets, such as California and New York City, we estimate that at least 65-70% of the attorneys who left law firms became unemployed within 18 months of starting their in-house jobs.

We also estimate that at least 60% of these same attorneys attempted to return to law firms after losing their jobs inside corporations. Out of this 60%, we estimate that less than 20% landed at law firms even arguably approaching the prestige level of the law firms they left to go in-house and that less than 50% were successful in getting another job with a law firm at all. A majority of these attorneys were graduates of top law schools coming from America's best law firms. The thought that they would ever be unemployed or have a difficult time locating a position was something that was incomprehensible to them and their families when they went in-house. Additionally, most of these same attorneys probably never comprehended that the companies they joined would be anything other than the next eBay, Yahoo!, or Amazon.com when they signed on.

While the above discussion illustrates a historical aberration, to a lesser extent, this pattern has been repeated throughout America every year for the past several decades as accomplished attorneys leave large law firms to go in-house and then for whatever reason attempt to return to law firms. Even in the best of times, companies may cut back their legal departments, go out of business, merge, or relocate. Or the in-house attorney may reach the decision that he/she wants to return to a law firm. Even if the economy is not in dire straits, most of these in-house attorneys will have a very difficult time returning to a significant law firm ever again. The reasons for this are related to the way law firms function as institutions and the expectations attorneys have for other attorneys in the law firm environment.

Law firms have a traditional set of expectations for attorneys. Lawyers inside large law firms are expected to go there and specialize quickly. Associates are expected to work hard and impress partners for 7 to 11 years, develop skills in relating with clients, and then make partner, take a counsel position, or move to a smaller firm. Throughout your time in a law firm, it is expected that:

- you will become increasingly competent in your work;

- you will be given increased responsibility;

- because of your developing skills and efficiency, your billing rate will increase each year;

- the firm's clients will rely upon and trust you to an increasing degree;

- you will develop more and more contacts, which you will be able to leverage into portable business.

- you will develop management skills and be able to supervise younger attorneys and paralegals.

Each step of the way, you are growing in a law firm's eyes.

It is especially problematic for an attorney to go in-house before getting at least four to five years of experience in a law firm. There, attorneys are trained and developed to become the best at what they do. As a young associate, you will typically work for mid-level or senior associates who will supervise you as you become increasingly competent. In most large law firms, the work you do is funneled up the chain of command and reviewed by partners to ensure the best possible work product. Every step of the way, a system of checks and balances is in place inside law firms to ensure that each lawyer produces outstanding work product. This, in turn, creates very good lawyers over time. Once an attorney goes in-house, he/she is unlikely to be supervised with this chain of command. Incredibly, in-house attorneys may even find poor work they do praised by outside law firms representing the company. Very few law firms ever criticize the work product of the in-house counsel of their clients. In-house attorneys represent revenue for the law firm that works for them, and law firms praise these in-house attorneys in the hopes of making these same attorneys feel good about themselves.

While there are certainly exceptions, once you go in-house, you are likely to become more of a generalist than a specialist. While the idea of being a generalist may be something that appeals to you, you also need to understand that the skills of a generalist will certainly not serve you well if you ever choose to go back to a law firm. Most law firms demand their attorneys specialize very early in their careers and continue as specialists in one practice group or another throughout their careers. As a generalist, you will be an expert in nothing. While you may find it more interesting to participate in different types of work, over time, you will simply be making yourself increasingly unmarketable to law firms.

Going in-house is something that jeopardizes the type of growth law firms expect attorneys to demonstrate throughout their careers. In short, law firms want attorneys to be committed to their methods of practicing law. Going in-house is not an action that law firms consider demonstrates your commitment to their method of practicing law. When you decided to go in-house, you radically put yourself off the track of training, growth, and development from a law firm's perspective. More significantly, you have sent the message to future potential law firm employers that you are not committed to their way of practicing law.

- See Beware! Once You Start Working in a Law Firm, If You Leave You Will Almost Certainly Not Be Able to Return for more information.

None of this is to say that you will never work in a law firm again if you go in-house. Many patent prosecutors, real estate attorneys, and other types of attorneys can become extremely specialized and receive excellent training in an in-house environment. There are, in fact, some very well respected in-house legal departments throughout the United States. In addition, if you reach the role of a general counsel in an important corporation (such as Disney or General Motors), you may actually become an extremely hot commodity among law firms because of your connections and the fact that you will likely be able to parlay this into significant business for the law firm once you join it. Many attorneys have successfully moved from important in-house legal environments to partner roles within the most significant international law firms after several decades in-house.

B. You Are Unlikely to Reap an Economic Windfall if You Go In-House

Many attorneys who went in-house during the tech boom were under the impression that they were invincible. Some were. It was not uncommon for third- or fourth-year associates in the Bay Area who went in-house from 1997-1999 to have cashed out stock options worth $1,000,000 or several times more after less than two years in an in-house environment. This happened enough times that many attorneys were under the impression that if they went in-house, this result was all but inevitable. What these attorneys were able to achieve with their careers in such a short period of time was nothing less than remarkable. These results were also unparalleled at any other time in the history of the legal profession.

Corporate attorneys, in particular, were in massive demand, and they were receiving calls—often several times per day—from recruiters seeking to place them in both corporations and law firms. Wanting fewer hours and stock options and having a certain vision of what going in-house meant, attorneys flocked to start-up companies (often ones with no revenue model) in the belief that they would quickly be rich. The fact is, however, that these success stories were (and continue to be) less common than believed.

How much does an in-house attorney make? While the salary of an in-house attorney can vary widely, we would estimate that fewer than 1 in 50 attorneys who left prestigious law firms ever ended up making more in-house (through a combination of stock options and salary) than they would have made had they remained in their respective law firms and not gone in-house. None of this even takes into account that a substantial number of these attorneys who did not experience fortune after going in-house left the practice of law completely after being unable to successfully find alternative legal employment after losing their in-house positions. In terms of a cost-benefit analysis, if you were to analyze the potential incomes these attorneys gave up over the courses of their legal careers by going in-house, the differential between the numbers would likely be staggering.

If you stay in the law firm environment for an extended period of time, there is a strong likelihood that you will be in a position to be financially independent after a couple of decades. Very few attorneys in this world achieve significant wealth in a short time span through the "IPO lottery" or the equivalent. While some people reason that lawyers in private practice have a ceiling in terms of compensation, the average salary for one still far exceeds the salaries of most Americans. At some of the biggest firms, associate- and partner-level paychecks can be enormous. None of this occurs within even a year or two for most attorneys and you should not treat your legal career like a lottery ticket.

While we do not do so anymore, at BCG Attorney Search, we used to do in-house placements at a time when the demand for in-house attorneys at start-up companies was at its peak. The following story illustrates one memorable meeting we attended for a start-up company that wanted us to assist it in locating a general counsel. At the outset, it is important to note that this particular story was atypical. The story nevertheless demonstrates the tremendous amount of greed and naiveté that characterized the rush of attorneys to the in-house legal market at that time. I also believe this story illustrates the shortsightedness of many attorneys who continue to go in-house to this day without realizing the potential consequences of doing so.

- The next H&R Block? In 2000, I was invited by a very important Bay Area law firm to come to a meeting being held by one of its clients. The company was seeking a general counsel and had invited me to the meeting because it wanted me to learn more about it in order to conduct the search. This internet company dealt with the accounting industry and had been started by a foreigner with no knowledge whatsoever of the accounting industry (he was a nuclear engineer). The company had recently received approximately $10,000,000 in seed funding from a venture capital firm. Despite the fact that the company had never brought in a single dollar in revenue, people were excited about it.

The meeting started early in the morning, and throughout the day, none other than a former US senator, the managing partner of a major international accounting firm, and several important partners in this particular law firm (the "Board") enthusiastically endorsed the company and exchanged ideas about how it was going to take over the world. The law firm, which was also charging the client by the hour, had received significant stock options in the company, and just about everyone else in the room had too. My payment for finding the general counsel was going to be in stock options as well. Everyone had options, even the guy who had been hired to write the business plan!

About six hours into the meeting, I realized that something was terribly wrong:

"If I understand you correctly," I interrupted, "this company is going to allow the average Americans to post the fact that they need their tax returns done on your website, and accountants are going to bid on the right to do each individual's tax return until the lowest price is reached?"

"Yes, exactly!" Everyone in the room nodded in unison and enthusiastically. "People will put in their credit card numbers and be charged for the tax return immediately once the auction is over. We will take 5% as a fee for brokering the transaction and forward the other 95% to the accountant within 90 days and in the interim make money off the 'float.' The float alone will represent millions of dollars per year. Our projections indicate that over 5% of Americans with access with a computer will be using the service within two years."

"The people will not have the right to choose their accountant?" I asked.

"No, of course not. It's a free market. The lowest-priced accountant will be the one who does the work. People will also have the ability to set the highest price they are willing to pay for the tax return, a 'reserve.' This website will make accounting more efficient and enable centralization in the industry. It's a win-win situation for everyone."

"What if the accountant does a bad job?" I asked.

"Well, if the person is unhappy with his/her tax return, we will kick the accountant out of our membership and not pay the accountant for the work. The accountant has every incentive to do a good job."

I was not invited back after I explained to the Board that I believed the business made absolutely no sense. The idea of paying the cheapest possible accountant to do your tax return was not something I believed would ever work. I was not invited back, nor was I asked to do the search for their general counsel, nor was I ever given stock options. Instead, a naive fourth-year attorney inside the law firm where the meeting was held begged for the job and was offered it.

He worked as general counsel with the promise of stock options for $60,000 a year (less than the $130,000 he was earning at the law firm at the time). Four months after taking the job, the company reduced his salary to $30,000 a year because it told him it did not have the money to pay him more. Within nine months of starting work, he was let go when the company went out of business. Stock options? Tax returns? If memory serves me correctly, I do not think a single person ever had his/her tax return performed on the reverse auction site despite millions of dollars in development costs.

This same attorney then tried to go back and get a position with a law firm. He was entirely unsuccessful. Six months after getting laid off, he accepted a part-time contract position with a small publishing company doing in-house legal work for $35 an hour. This story is not unique. In fact, this story is the norm for a large proportion of attorneys who went in-house during the economic boom. What makes this story so sad is that this attorney, like many before and after him who have had the same results with their careers after going in-house, was among the more accomplished attorneys in his law firm with some of the highest prospects before he went in-house.

While the tech boom is now over, a fair number of attorneys continue to express a desire to get into a company for stock options or in the hopes of a windfall at the IPO stage. Incredibly, many attorneys' desires to get rich quick are so strong that even in the face of what has been an economic meltdown in the in-house market, some are now expressing the idea that it is a good time to get in because stock prices are so low, they can only go higher.

Click Here to Find Out What In-house Attorney Positions Actually Pay.

Within the past few years, that dream came crashing down for many lawyers who left their prestigious law firms in an attempt to make it big. Many of these attorneys have now been looking for a job—any legal job—for more than a year. The Cinderella stories of massive economic gain have all but dried up, and lawyers from in-house environments continue to attempt to return to private practice in droves.

Most large law firms have been around for decades, sometimes more than a century. For the most part, they are not going anywhere, even in a bad economy. The economic stability of law firms is unmatched by many other institutions, including most companies where an attorney might like to go in-house. Although law firms occasionally go under, they are, in general, much more stable than companies in other industries

This is especially true of the full-service firm. When the economy is good, the real estate and corporate lawyers are busy. When it turns sour, the bankruptcy and litigation lawyers can pick up the slack in terms of billing and profitability. Most law firms diversify their client base to such an extent that the failure of any one or two clients will not compromise the bottom line. Law firms are built for survival in even the toughest economy.

Obviously, it is not accurate to state that law firms do not go out of business. However, when a law firm such as Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison goes out of business, it is considered a monumental event in the legal community because it is so exceedingly rare for law firms to go out of business. Conversely, companies the size of even the largest law firms go out of business every day of the week. Most of these companies have in-house attorneys.

There is a saying: "If it looks too good to be true, it probably is." While most attorneys out there have heard this saying, it bears repeating. Anything that produces strong economic results generally does so because it is providing value and doing so over an extended period of time. It is important to realize that whatever path you choose with your legal career, you will only be highly compensated if both you and your organization are providing value in the marketplace.

C. It is Very Difficult to Get Another In-House Job Once You Go In-House

The difficulty of getting a job in another law firm once you have gone in-house may be surpassed only by that of getting another in-house counsel position. Typically, some of the most attractive candidates to in-house employers are the attorneys inside the law firms who handle their legal work. These attorneys are already familiar with the company, have established relationships with key players inside it, and are trusted legal advisers who cost the company a great deal of money. The idea of bringing these already trusted attorneys inside the company and saving it money is something that is certainly an attractive prospect to many companies. In our experience, most attorneys who go in-house are hired by their former clients.

In theory, it would be excellent if everyone could go to work for one employer and remain there until retirement. Nevertheless, the United States is not a socialistic or communist country, and companies go out of business, legal departments are downsized, and companies decide they no longer want an in-house legal department. You will be extremely unlikely to remain in the same in-house job throughout your career and will in all probability need to seek alternative in-house employment at some point. In searching for your next in-house legal job, you will not have the luxury of being a bright-eyed attorney being wooed by your client. Instead, you will need to hit the street and start tracking down these jobs on your own. When you have a family, friends in the area, kids in a local school, and a mortgage, this may not be something that appeals to you all that much.

Many attorneys who left law firms to go in-house (and did not go in-house with their clients) spent years searching for in-house positions before they found one. These same attorneys, who are most often at the associate level, are often quite eager and convey a surprising level of enthusiasm for working in-house to potential employers. When you attempt to find another in-house position, you are entering a tremendously competitive market, where there are likely to be numerous people competing for the same position. As an attorney inside a law firm, you are arguably more attractive to in-house employers. If the search for an in-house position can take years when you are inside a law firm, imagine how long it will take when coming from an in-house position?

If you search job boards, legal recruiter ads, or other sources where in-house jobs are typically listed, it should be no surprise that there are far more law firm than in-house positions listed. For example, if you go to most cities in the United States of between 100,000 and 200,000 people, there are likely to be more than 100 law firms of more than 10 attorneys. In this same market, there may be fewer than 10 companies that even employ in-house attorneys, and the number of attorneys these companies hire is likely to be quite low.

D. Once You Go In-House, Your Skills Are Likely to Deteriorate

Very few attorneys realize just how much their skills are likely to deteriorate once they go in-house. A large portion of the responsibility of many in-house attorneys is to farm out challenging work to the appropriate law firms. Therefore, once you go in-house, you will often cease doing sophisticated legal work and instead merely hand it off to law firms. For some attorneys, this is the ideal job. For others, this is not ideal because they no longer work directly on challenging legal work.

If you are at a company doing an IPO, an outside law firm—and not you—will likely be responsible for it. If your company is involved in significant litigation, almost always an outside law firm—and not you—will be the one drafting the motions, doing discovery, and going to court. All of this should make it obvious that a great deal of the learning and refinement of your legal skills that occurs inside a law firm stops once you go in-house. It is unlikely you will stay abreast of the law once you are in-house because you will have no reason to. Because you will be doing less hands-on work and will be exposed to fewer nuts and bolts of practicing law, your skills will gradually deteriorate.

E. You May Have to Work as Hard In-House as in a Law Firm

With some exceptions, in-house attorneys most often do not have to work as hard as their counterparts at firms. This is one of the better reasons for going in-house. It is your life, and being in-house can release you from much of the pressure of the billable hour requirement and other stresses of being in a law firm. In addition, being in-house typically has more predictable hours. We have no doubt that working in a law firm can often be incredibly stressful. In large law firms, many attorneys are plagued by divorce or substance abuse and spend little time with their children. Indeed, many attorneys in large law firms consider anything that does not relate directly to the practice of law as something that is a distraction, even if it is spending time with family. An in-house environment can often give you your life back.

However, a job in-house is often not the utopian environment described above. We often encounter lawyers whose primary goal in a career change is to reduce the pressure of billable hour requirements that seem to be only associated with private practice. Depending on your career and life goals, it is often perfectly reasonable to seek situations that will require something less than the typical billable hour requirements of an associate at a busy law firm. However, we do not agree that private practice necessarily means an unreasonable grind nor should one expect a laid-back lifestyle in every in-house position.

General Counsel and associate general counsel of large corporations often work the same hours as lawyers in private practice, which sometimes include late-night and weekend work. Many in-house departments of corporations are set up like law firms, where different departments within the company are considered clients, and in-house counsel is required to bill and record how he spent his time with the internal clientele. For the companies that do not require their lawyers to bill their time, a lawyer working long hours has no record for the purpose of year-end productivity bonuses, as law firms do.

Additionally, the typical in-house work environment is changing and may no longer be everything an attorney fleeing firm life is seeking. The most recent annual survey of in-house attorneys by Corporate Counsel shows that despite myths to the contrary, the in-house environment is slowly morphing into somewhat of a friendlier law firm grind over the last few years. Everything from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act to the recessionary economy has contributed to a more stressful work environment for in-house attorneys.

With corporate budgets going down, more pressure is being put on in-house attorneys to bring work in-house rather than farm it out to law firms. When that work comes in, though, fewer attorneys are being asked to handle it. In-house downsizing is one way that corporations are choosing to trim the budget fat, meaning in-house attorneys are among the casualties of the economy. Those in-house attorneys surveyed by Corporate Counsel say this piling on of work has led to the late nights and weekends that many sought to avoid by making the in-house decision.

While the work is increasing and the perks are decreasing, in-house attorneys surveyed in the article overwhelmingly still enjoy their positions. Many who are currently employed are not looking for new positions and/or feel that the layoffs have passed. Also, the work is able to hold the interest of the majority of employees, and the client contact and increased sense of camaraderie among colleagues still remain.

On the other hand, law firms are increasingly amenable to flextime, reduced hours, or telecommuting situations for valued lawyers. In the end, it is impossible to generalize what the time and billable hour requirements are for either law firms or corporations, and it is simply incorrect to assume that the grass is greener on the other side. The reality is that most lawyers with sophisticated practices work hard, whether in private practice or in-house. There are as many distinctions to be made between lawyers practicing with law firms as there are differences in the day-to-day lives of prosecutors, general counsel, and large-firm associates.

One of our recruiters was recently corresponding with a friend who had just received an in-house position. This attorney was three years out of a top Ivy League law school and working for arguably one of the top two or three law firms in the United States:

- Are you sure about the in-house thing?

In short, I do not think that in-house positions are usually a good idea for a good lawyer at your level. You will be making a decision to be an employee rather than a business owner; to turn over control of your destiny to a board of directors and stockholders, rather than controlling it yourself; and to limit your financial upside drastically. Your ability to come back to a law firm after leaving for an in-house job is almost nil as well, so you should kind of look at the option with the same sort of circumspection that you might view a vasectomy: It may be reversible, but you'd better be darned sure about it anyway.

On that note, I just got a call earlier from a guy who left a big-time firm as a fourth-year to go in-house at a major independent company. It had a change of general counsel five months later, and he was out of a job. The new general counsel wanted to farm the work out. His firm won't take him back, and I had to tell him that I can't get him a job.

There are a lot of good law firms out there that might solve your problems without the negatives of the in-house world. I would recommend looking at those options first. Keep your option to go in-house until you learn you can't go further in a law firm. If you can make partner in a good one, you might be a general counsel when you make that switch. As a seventh- or eighth-year, you could be an assistant general counsel reporting to a named executive officer (rather than another lawyer only). That's a much better position.

We encourage any lawyers considering a career change to avoid generalizations and preconceived notions of what it means to be practicing with a law firm and instead to focus on what jobs are best suited to their particular credentials and abilities. We've heard the success stories for in-house positions—they do happen. However, we also believe that law firms get an undeserved bad rap among lawyers.

You need to carefully weigh your options before going in-house. There is a chance that going in-house could be the perfect career decision for you. Like everything in life, you need to maximize your long-term self-interest. If, when all is said and done, going in-house is likely to maximize your self-interest, then it is probably the right thing to do.

Comments

- Harrison, I read with interest your article entitled "The 'Dark Side' of Going In-house" --- very well written and mostly accurate. Thank you for sharing your insights. Regards, Rami

- Harrison, Just a quick note to thank you for sending me your article disclosing the negative sides of going in-house and how going in-house could be the worst move for a good lawyer. Thank you for also taking the time to identify better alternatives. Many were gems. That took imagination and insight and wisdom. But most of all, it took bravado to tell it like it generally is. You are a good man! Don't ever change. Continued best wishes! Getmjc@gmail.com

Read Related Articles

- Working as an In-House Corporate Counsel

- Going In-House

- In-House Counsel: Life in the Corporate Wing

- The Life and Career of an In-House Attorney

- What Do In-House Attorney Positions Pay?

- Tips on Preparing Yourself for the Interview for an In-House Counsel Job

- Pros and Cons: In-house vs. Law Firm Practice

- Going In-house? Why You May Be Saying Goodbye to Law Firms for Good

- Seven Questions Attorneys Must Ask Themselves Before Going In-House

- Is an In-House Job Right for You? Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions About In-House Careers

Click here to contact Harrison

About Harrison Barnes

No legal recruiter in the United States has placed more attorneys at top law firms across every practice area than Harrison Barnes. His unmatched expertise, industry connections, and proven placement strategies have made him the most influential legal career advisor for attorneys seeking success in Big Law, elite boutiques, mid-sized firms, small firms, firms in the largest and smallest markets, and in over 350 separate practice areas.

A Reach Unlike Any Other Legal Recruiter

Most legal recruiters focus only on placing attorneys in large markets or specific practice areas, but Harrison places attorneys at all levels, in all practice areas, and in all locations-from the most prestigious firms in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., to small and mid-sized firms in rural markets. Every week, he successfully places attorneys not only in high-demand practice areas like corporate and litigation but also in niche and less commonly recruited areas such as:

- Immigration Law

- Workers Compensation

- Insurance

- Family Law

- Trust and Estate

- Municipal law

- And many more...

This breadth of placements is unheard of in the legal recruiting industry and is a testament to his extraordinary ability to connect attorneys with the right firms, regardless of market size or practice area.

Proven Success at All Levels

With over 25 years of experience, Harrison has successfully placed attorneys at over 1,000 law firms, including:

- Top Am Law 100 firms such including Sullivan and Cromwell, and almost every AmLaw 100 and AmLaw 200 law firm.

- Elite boutique firms with specialized practices

- Mid-sized firms looking to expand their practice areas

- Growing firms in small and rural markets

He has also placed hundreds of law firm partners and has worked on firm and practice area mergers, helping law firms strategically grow their teams.

Unmatched Commitment to Attorney Success - The Story of BCG Attorney Search

Harrison Barnes is not just the most effective legal recruiter in the country, he is also the founder of BCG Attorney Search, a recruiting powerhouse that has helped thousands of attorneys transform their careers. His vision for BCG goes beyond just job placement; it is built on a mission to provide attorneys with opportunities they would never have access to otherwise. Unlike traditional recruiting firms, BCG Attorney Search operates as a career partner, not just a placement service. The firm's unparalleled resources, including a team of over 150 employees, enable it to offer customized job searches, direct outreach to firms, and market intelligence that no other legal recruiting service provides. Attorneys working with Harrison and BCG gain access to hidden opportunities, real-time insights on firm hiring trends, and guidance from a team that truly understands the legal market. You can read more about how BCG Attorney Search revolutionizes legal recruiting here: The Story of BCG Attorney Search and What We Do for You.

The Most Trusted Career Advisor for Attorneys

Harrison's legal career insights are the most widely followed in the profession.

- His articles on BCG Search alone are read by over 150,000 attorneys per month, making his guidance the most sought-after in the legal field. Read his latest insights here.

- He has conducted hundreds of hours of career development webinars, available here: Harrison Barnes Webinar Replays.

- His placement success is unmatched-see examples here: Harrison Barnes' Attorney Placements.

- He has created numerous comprehensive career development courses, including BigLaw Breakthrough, designed to help attorneys land positions at elite law firms.

Submit Your Resume to Work with Harrison Barnes

If you are serious about advancing your legal career and want access to the most sought-after law firm opportunities, Harrison Barnes is the most powerful recruiter to have on your side.

Submit your resume today to start working with him: Submit Resume Here

With an unmatched track record of success, a vast team of over 150 dedicated employees, and a reach into every market and practice area, Harrison Barnes is the recruiter who makes career transformations happen and has the talent and resources behind him to make this happen.

A Relentless Commitment to Attorney Success

Unlike most recruiters who work with only a narrow subset of attorneys, Harrison Barnes works with lawyers at all stages of their careers, from junior associates to senior partners, in every practice area imaginable. His placements are not limited to only those with "elite" credentials-he has helped thousands of attorneys, including those who thought it was impossible to move firms, find their next great opportunity.

Harrison's work is backed by a team of over 150 professionals who work around the clock to uncover hidden job opportunities at law firms across the country. His team:

- Finds and creates job openings that aren't publicly listed, giving attorneys access to exclusive opportunities.

- Works closely with candidates to ensure their resumes and applications stand out.

- Provides ongoing guidance and career coaching to help attorneys navigate interviews, negotiations, and transitions successfully.

This level of dedicated support is unmatched in the legal recruiting industry.

A Legal Recruiter Who Changes Lives

Harrison believes that every attorney-no matter their background, law school, or previous experience-has the potential to find success in the right law firm environment. Many attorneys come to him feeling stuck in their careers, underpaid, or unsure of their next steps. Through his unique ability to identify the right opportunities, he helps attorneys transform their careers in ways they never thought possible.

He has worked with:

- Attorneys making below-market salaries who went on to double or triple their earnings at new firms.

- Senior attorneys who believed they were "too experienced" to make a move and found better roles with firms eager for their expertise.

- Attorneys in small or remote markets who assumed they had no options-only to be placed at strong firms they never knew existed.

- Partners looking for a better platform or more autonomy who successfully transitioned to firms where they could grow their practice.

For attorneys who think their options are limited, Harrison Barnes has proven time and time again that opportunities exist-often in places they never expected.

Submit Your Resume Today - Start Your Career Transformation

If you want to explore new career opportunities, Harrison Barnes and BCG Attorney Search are your best resources. Whether you are looking for a BigLaw position, a boutique firm, or a move to a better work environment, Harrison's expertise will help you take control of your future.

Submit Your Resume Here to get started with Harrison Barnes today.

Harrison's reach, experience, and proven results make him the best legal recruiter in the industry. Don't settle for an average recruiter-work with the one who has changed the careers of thousands of attorneys and can do the same for you.

BCG Attorney Search matches attorneys and law firms with unparalleled expertise and drive, while achieving results. Known globally for its success in locating and placing attorneys in law firms of all sizes, BCG Attorney Search has placed thousands of attorneys in law firms in thousands of different law firms around the country. Unlike other legal placement firms, BCG Attorney Search brings massive resources of over 150 employees to its placement efforts locating positions and opportunities its competitors simply cannot. Every legal recruiter at BCG Attorney Search is a former successful attorney who attended a top law school, worked in top law firms and brought massive drive and commitment to their work. BCG Attorney Search legal recruiters take your legal career seriously and understand attorneys. For more information, please visit www.BCGSearch.com.

Harrison Barnes does a weekly free webinar with live Q&A for attorneys and law students each Wednesday at 10:00 am PST. You can attend anonymously and ask questions about your career, this article, or any other legal career-related topics. You can sign up for the weekly webinar here: Register on Zoom

Harrison also does a weekly free webinar with live Q&A for law firms, companies, and others who hire attorneys each Wednesday at 10:00 am PST. You can sign up for the weekly webinar here: Register on Zoom

You can browse a list of past webinars here: Webinar Replays

You can also listen to Harrison Barnes Podcasts here: Attorney Career Advice Podcasts

You can also read Harrison Barnes' articles and books here: Harrison's Perspectives

Harrison Barnes is the legal profession's mentor and may be the only person in your legal career who will tell you why you are not reaching your full potential and what you really need to do to grow as an attorney--regardless of how much it hurts. If you prefer truth to stagnation, growth to comfort, and actionable ideas instead of fluffy concepts, you and Harrison will get along just fine. If, however, you want to stay where you are, talk about your past successes, and feel comfortable, Harrison is not for you.

Truly great mentors are like parents, doctors, therapists, spiritual figures, and others because in order to help you they need to expose you to pain and expose your weaknesses. But suppose you act on the advice and pain created by a mentor. In that case, you will become better: a better attorney, better employees, a better boss, know where you are going, and appreciate where you have been--you will hopefully also become a happier and better person. As you learn from Harrison, he hopes he will become your mentor.

To read more career and life advice articles visit Harrison's personal blog.