Harrison Barnes' Legal Career Advice Podcast - Episode 78

- Ascending to the role of a partner is a dream for any associate.

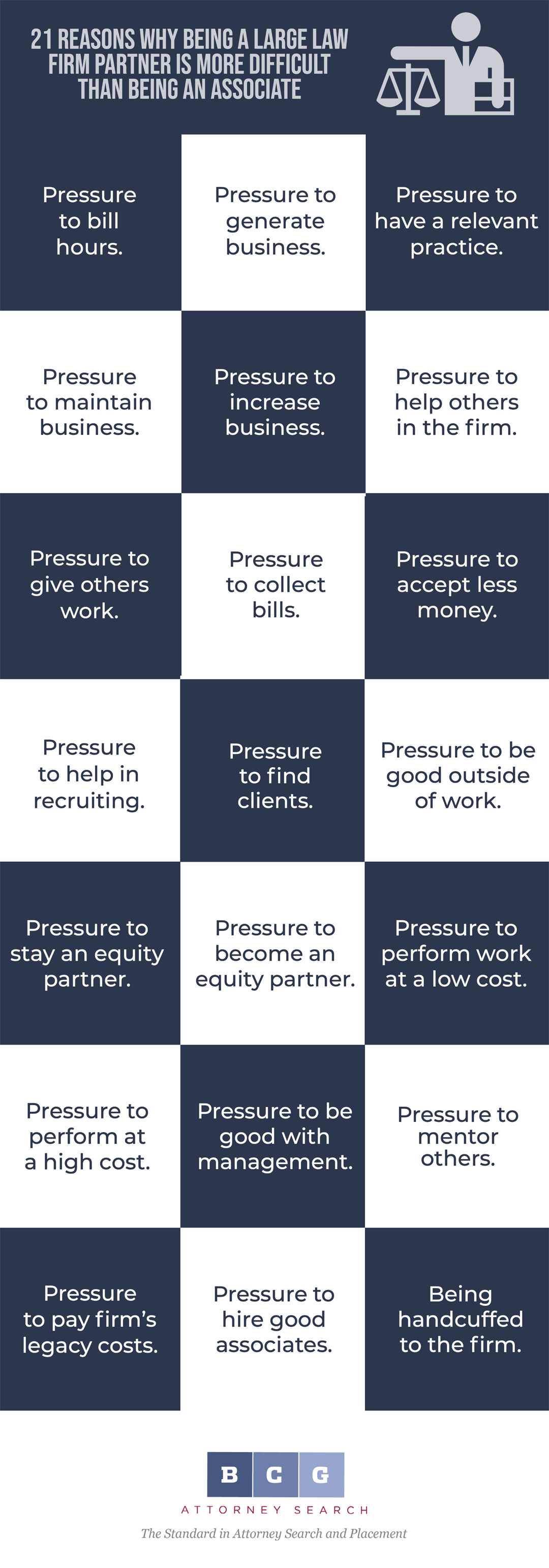

- However, there are challenges to being a partner that an associate may not know about.

- Keep reading to find out what those challenges are.

Summary: Learn about the challenges partners face inside law firms in this article.

For some strange reason, many young attorneys believe that their troubles will disappear when they are elevated from an associate to a partner in a large law firm.

|

| Harrison Barnes |

That could not be further from the truth.

The stress and realities of being a partner at a large, modern American law firm are quite profound. In fact, I would say that the self-esteem of the average, well-educated first-year associate is better than that of the majority of partners. While an associate may suffer criticism for the quality or quantity of the work he or she produces, the situation is turned on its head and becomes far more pronounced for partners. The pressures on partners in large law firms are so severe and the skills required are so different from associate skills that few attorneys are capable of handling them. Too many lawyers end up “making partners” even though they are unprepared for the task.

Being a law firm partner in a large American law firm is one of the most demanding jobs there is. While many partners enjoy practicing law, a large number do not—and are looking to escape. While associates looking to escape ask about in-house jobs, it is partners looking to escape who ask about in-house jobs most of all—even partners with businesses. There is no letting up on the pressures that partners face and the pressures just keep increasing year after year. In fact, because there is so much gray area regarding how partners are compensated, advanced, and let go, and because of the inordinate amount of politics that directly affect the careers of partners, many partners look back on their associate days as times when life was far, far easier. This article is about some of the challenges partners face inside law firms.

1. Pressure to Bill Hours

Partners in all law firms are under continuous, significant pressure to get work and bill hours. It does not matter where the work comes from. It could come from other partners in the firm or clients. The pressure to get work is never-ending and if a partner has even one bad year of low billable hours the partner may lose his or her job. Partners in all law firms know that if they have a few slow months of work, it is a very bad sign for them. They have seen what happens to other partners when their work slows down and partners know that their work must never stop, or their careers could be over.

I receive resumes and phone calls from partners in major American law firms each day who have lost a major client or two, or whose firm has lost a major client or two, or who no longer have work because the partner is on the outs with a more important partner who used to give that partner work, or who was left behind when a group left the firm for a new firm. I always ask how many hours the attorney is billing, and when I hear numbers like “1,200” I get very worried. In most instances, when you hear a number like “1,200” you can pretty much assume that the attorney will not be at the firm longer than six to eight months. They are on occasion, but not often. Sometimes they get lucky, of course, and everything turns around; I have seen this happen occasionally.

Depending on the firm, if a partner does not have a lot of his or her own work the partner is reduced to seeking work from other partners who do have it. This can be a precarious situation, because the partner may be getting work from only one or a few partners in the firm. If the partner upsets these attorneys, then he or she is going to be in a difficult situation. If the generating partner leaves the firm or loses a major client, the service partner can be adversely affected.

It is much more difficult for partners to get work from other partners than it is for associates to get work from other partners. Associates have far lower billable hour rates and associates are given work to save money for clients and to take busy work away from partners. Because partners are more expensive, other partners are less likely to give them work when it is cheaper to give it to associates. Also, because most law firm compensation systems are such that partners make more money when they do their own work than when they give it to others, partners prefer to do work for their clients rather than give the work to other partners.

The constant pressure to get work means that the partners who succeed have one of a few qualities. Either they are very talented practitioners to whom colleagues are eager to give work or they are perpetual salesmen and saleswomen who can consistently generate work through networking internally in their firm and externally outside. They need people to constantly give them work and they always need to be selling.

Most careers of partners end in the law firm world when they are unable to get enough billable hours to stay busy. They might get frozen out or their firms might lose business. For whatever reason, they do not have enough business. This is the number one reason why partners start looking for work and lose their positions. Partners in this situation comprise the majority of partners looking for work in the legal market at any given time. These partners will put together business plans and approach law firms in the market with the prospect that they have the skills to do the work. It can work if they find a busy firm, but it is an uphill battle.

In some law firms, partners are expected to bill 2,500 hours or more per year—with many billing far beyond that amount. They need to find continuous access to work to generate hours at these levels. As I mentioned earlier, it is generally much more difficult for partners to get billable hours than it is for associates.

2. Pressure to Generate Business

In addition to the constant pressure to get work, partners in most law firms are under continuous, significant pressure to generate business. Because they know they cannot always rely on other attorneys in the firm to give them work, the next most logical step is for them to get their own business—which they all desperately want.

These early stages of a partner’s career involve the attorney doing everything in his or her power to get business. In many law firms, young partners will spend a few hours on the phone each day cold calling potential clients to try and get new work. Young partners who are unable to generate significant business will find their prospects quite limited in their firms and will become part of a cycle of dependence on others for work. This means less independence, less employment security, lower income, and more difficulty keeping their hours up.

While an associate has the luxury of getting work from others, partners need to have their own business to have any control over what happens with their careers. In some large law firms, the only work partners can count on is the work that they bring in.

3. Pressure to Maintain Business

Once an attorney gets business, the attorney will be evaluated based largely on that talent and on his or her ability to continue to generate business. While partners in this situation may have some “give” in this area, in general, if their business falls from say $3-million to $1-million, they will begin to feel a large amount of pressure from management. Their income might also be cut quite dramatically.

It is also very difficult for many partners to maintain business. The relationships that generate business are often with general counsels of various companies. If a general counsel changes, a partner can suddenly lose a major client. I have seen entire groups of ten or more attorneys lose their jobs at major law firms with the loss of a large client. As discussed later, the ability to generate and maintain business also is exacerbated at large firms because of client conflicts issues.

Associates are not under pressure to maintain business.

4. Pressure to Increase Business

Once a partner brings in business, most law firms will start pressuring that partner to bring in additional business year after year. These goals are always something in the back of the mind of most partners, and partners know that they are only as good as their last year of collections. In most law firms, partners will be given new goals each year to get more and more business.

5. Pressure to Help Others in the Firm Generate Work

Even if they do not necessarily get credit for it, partners are also expected to help others in the firm generate work and stay busy. They may be brought in to assist in developing business if they have expertise in a subject matter that would be helpful to have on a team. They may assist in preparing proposals and giving various pitches to various potential clients.

The work of cross-selling and of being part of a multi-faceted large law firm team that can serve the most important and best-paying clients is valuable, but this work takes time and takes partners away from more immediate billing needs. Moreover, cross-selling efforts often lead nowhere.

6. Pressure to Give Others Work

If a partner has a decent amount of business, that partner will also be evaluated based on his or her ability to give others in the firm work. Partners with businesses will be under a good deal of pressure to keep the people close and loyal to them busy. This could be associates, counsel, or partners beneath them.

People will be loyal to a partner to the extent that the partner can keep others busy and working. Many partners are evaluated and compensated based on formulas, which takes into account the amount of work they give to others—and how many other attorneys they give work to. Associates may have been hired to work with a partner specifically, and the partner may be expected to keep them busy.

Obviously, associates are not under a lot of pressure to give others work.

7. Pressure to Collect Bills

Most partners in large law firms are always under pressure to collect bills. This is a constant stress for many partners, and the management typically hounds partners when bills are not paid promptly. Bill collection is an unglamorous, stressful, and time-consuming process. It strains relationships with clients and detracts partners from doing the real work they are trained to do.

8. Pressure to Accept Less Money from the Firm

Once partners get significant business, they enter a spiral where the business they bring in and their compensation are continually subject to negotiation and attack by the law firm. This creates a whole set of different variables that are discussed below. In most cases, a partner’s compensation is always less than he or she believes it should be.

If a partner has an extraordinarily good year, the law firm may pay that partner the same as it did the previous year with the promise that if the partner has a slow year in the future, his or her compensation will be kept the same. But such promises are not always honored. There are very few instances when partners receive as much money as they believe that they are entitled to.

Moreover, I have seen some major American law firms compensate partners without business less than those same firms compensate senior associates. It is all over the board and something that causes stress, uncertainty, and resentment among many law firm partners.

Associates in large law firms are paid a large salary regardless of whether or not they generate business.

9. Pressure to Have a Relevant Practice Area to the Firm

Some practice areas in large law firms become completely irrelevant and on the way out. Many large law firms are trying to get rid of labor and employment work, or certain kinds of labor and employment work (defending class actions, for example). Some law firms simply decide at various points in time that they no longer have an interest in a given practice area and phase it out. I have seen this happen with practices such as patent prosecution, labor and employment, and others.

Sometimes this is the result of economic shifts, or different management agendas, or other reasons, but it can be very stressful for partners to constantly worry that the practice area they have cultivated and spent years developing can get tossed aside because it is not the current flavor of the month.

10. Pressure to Help in Recruiting

Many partners are expected to assist law firms with recruiting, whether it is interviewing people in the office, traveling to law schools, or going to various events in the summer and throughout the year. Most of this work does not involve billable hour credit, and most of it is not that enjoyable for partners. Answering questions about what differentiates the firm culture and more is often something that gets old very quickly.

11. Pressure to Find Clients Where There Is No Conflict

Many partners in large law firms spend a few decades, or more, cultivating relationships with large clients and then when they bring them in have various conflicts that prevent the firm from accepting those clients. Sometimes partners are even asked to eliminate certain clients because the law firm wants to bring in another client.

Conflicts can create huge headaches for partners, and these conflicts directly affect the partner’s ability to be independent with a book of business. These conflicts can be more pronounced at the largest law firms with thousands of clients and potential conflicts. Retention isn’t only about numbers—Davis Wright Tremaine LLP proves that career development is equally vital.

12. Pressure to Look Good in the Community and Outside of Work

Much more so than for associates, partners are under pressure to look good in their communities and outside of work. To generate business and look good outside of work, many partners will volunteer to be on various committees and assume leadership roles outside of work. This takes up a lot of time and creates constant pressure to be seen outside of work. Most partners who successfully bring in a lot of business can do so by being highly visible outside of the office. In fact, many of the most successful attorneys I know are busy in various meetings outside the office two or more nights per week. The best attorneys do not always just go home at night after work—the “most important” part of their day starts when the workday ends. Perhaps they need to present a continuing legal education course, speak at a bar convention, attend a committee meeting, or show up at a networking event.

The importance of public image also carries other risks. I have seen partners lose their jobs for getting arrested after an argument with their wives and other similar instances outside of the office. Law firms value partners with a public image—it confers prestige and respect upon the firm and helps with clients and new business development—but law firms will quickly discard attorneys who make them look bad outside of the office.

13. Pressure to Stay an Equity Partner

Equity partners are one or two bad years away from becoming non-equity partners if they lose significant business. It is very common for law firms to “de-equitize” partners when they are not bringing in business, and this is highly embarrassing to the partners when this occurs. Once a partner becomes an equity partner he or she is terrified of losing this position and getting demoted to “de-equitized” status.

14. Pressure to Become an Equity Partner

Someone who is a non-equity partner feels constant pressure to generate business and become an equity partner. In many law firms, a non-equity partner may only be given a few years to get business before being shown the door, if he or she is unable to get business.

15. Pressure to Perform Work at a Low Cost

While an associate has the luxury of simply doing the work, a partner is often under marching orders from a client to do work at a low cost. Also, the partner knows that future work from a client will often depend on the partner’s ability to keep costs low. If the work gets too expensive, the client may go elsewhere—and most clients are somewhat cost-sensitive. This means that a partner may not want a lot of hours billed to certain clients and will do their best to keep costs low. To keep costs low, a partner may often be forced to write down their hours and write down the hours of associates and others. This will then create issues with the management of the firm.

16. Pressure to Perform Work at a High Cost

While facing pressure from clients to do work at a low cost, most law firms also create pressures for partners to do work at a high cost. Many law firms are consistently raising the billing rates of partners, and this makes it more and more difficult for partners to hold onto work. With very high and prohibitive billing rates, it also becomes very difficult for partners in many law firms to attract new clients.

The pressure to generate revenue also creates an atmosphere where many partners will “overwork matters” to get extra fees out of it. This includes assigning unnecessary research and repetitive work, and assigning work to associates whom they know will work longer hours than necessary. This is becoming common in law firms and it impacts the relationship partners have with clients and leads to the overall skepticism with which the business community now views large law firm billing practices.

17. Pressure to Be on the Right Side of Management

In many large law firms, compensation and other important matters that affect partners are decided by committees. Partners feel a lot of political pressure to get on the right side of the management and the people making these decisions. Most partners are constantly doing what they can to ingratiate themselves with various decision-makers inside the firm.

18. Pressure to Mentor and Train Others

Partners are often expected to mentor and train others. This means that after practicing for 30+ years, they are often expected to go to endless lunches with law students, young attorneys, and others when they would rather be working, or developing businesses. Also, they often need to show up at firm events even when they have no interest in being there so they can talk to people they know are unlikely to be there in a year or two.

Training young attorneys on elementary legal concepts also are not necessarily the most enjoyable task for most partner attorneys. The pressure to mentor and train others also means that partners need to review associates (and often other partners) and document their experience with different attorneys.

19. Pressure to Pay Legacy Costs of the Firm

Many law firms have huge legacy costs. These costs may include things such as pensions of partners long gone, massive salaries of partners negotiated during better times, office space no longer in use, and more. Legacy costs at some firms are so large that it creates a good deal of pressure on existing partners at the law firm—who need to generate the business and revenue to pay these legacy costs yet derive little if any benefit from them.

20. Pressure to Hire and Keep Good Associates

Law firm partners are generally under a lot of pressure to hire and maintain the best associates. This means that they often need to pay competitive salaries at the largest law firms, which is very expensive and creates corresponding pressures on other aspects of the business, like keeping client bills low enough to keep clients. To the extent they do have good associates, partners feel pressured to keep these associates around and (work permitting) hire more of them.

It is difficult for many law firms to hold on to associates due to morale issues, market pressures, and more. If a partner is unable to hold onto good associates to work on their matters, then the partner needs to do the work on his or her own. This takes up valuable time that the partner could be allocating towards business development activities or towards doing other work that is not necessarily appropriate for even the best associate.

21. Being Handcuffed to the Job and Firm

One of the more serious issues that affect partners is that the more money they make, the more their lifestyle grows to accommodate this spending. As their income requirements increase, they begin to feel trapped and need to make a certain amount of money, year after year, to pay for this lifestyle. These “golden handcuffs” prevent them from escaping and trying something different. They can no longer take risks if they hope to maintain this lifestyle (which often involves not just the partners but also spouses and children).

Most partners begin to feel very trapped after some time and have few other options other than to try and remain partners in their current firm, or another firm. After several years as partners, many partners have assumed such a lifestyle that they are unable to really even contemplate an alternate career—as many associates can.

What Is A Law Firm Partner?

Partner is a legally respected title in the legal, accounting, consulting, and financial industries, traditionally denoting co-ownership of a partnership in which each partner received a share of profits as "equity partners." Partners can also be shareholders in an entity where equity is held.

Lawyers who are partners are primarily responsible for generating the firm's revenue. Equity partnerships are governed by different standards for different firms. In many law firms, the partners are structured in two tiers, with some partners designated as "salaried partners" or "non-equity partners." These partners are allowed to use the "partner" title but are not entitled to any profits. Typically this is a "probationary" status for associates (or former equity partners whose revenue wasn't sufficient to warrant equity partner status). Firms often fail to disclose the difference between equity and non-equity partners to clients, although an equity partner might be paid three times as much as a non-equity partner billing at the same hourly rate. Attorneys who are not on track to become partners in America often call themselves "of counsel", whereas their British counterparts call themselves "Senior Counsel".

How Do Law Firm Partners Get Paid?

Make sure you understand what is being offered if you make the partnership cut. Learn how the profit pie in your firm gets sliced, and when you will receive it. Companies often pay their partners a draw then distribute their funds quarterly or annually.

There are two types of partnership in large law firms: equity and nonequity. A true partnership requires funding, so you'll have to contribute equity yourself. Assets, such as real estate, and liabilities, are owned by equity partners.

No-equity partnerships allow businesses to give their associates the title of partner while retaining equity ownership. In a non-equity partnership, you participate in profit sharing and gain the reputation of a partner without owning any company shares.

By May 27, 2021, the average Law Firm Partner salary in the United States will be $206,488. The salary range will usually fall from $167,944 to $253,076. Education, certifications, additional skills, and the number of years spent in your field can influence salary ranges widely.

What Happens When You Make Partners At A Law Firm?

During their early careers, most lawyers hope to be made partners. Nonetheless, if this is your objective, you need to know what being a partner means in this new legal corporate environment.

Typically, nonequity partners become partners with their firm after becoming partners. In the legal field, this is a relatively new concept. Since the 1980s, it's been used in some industries, but in the current business climate, it's taking off. In most law firms today, there are different tiers of partnership. In non-equity partnerships, job security is less. Non-partners often have greater job security. Their responsibilities are not the same as those of equity partners, who are expected to bring in a certain amount of revenue to the firm. If non-equity partners do not bring in enough new business, they can be discharged from the firm.

In essence, non-equity partners are middle managers and equity partners in training. Lawyers with a partner title get a higher salary and a better-sounding title, but in most other ways, they are no different from regular lawyers.

Equities partners, on the other hand, enjoy job security. Your job is secure as long as you continue to perform at the level your law firm expects from you. You are a professional who performs at a high level and has a good reputation in the legal community and in the community where you live.

Once someone has been named an equity partner, they are given a loan to become a part of the firm. In addition to their salary, they get a share of the profits made by the firm. In most cases, the cost of "buying-in" is in the thousands of dollars. Individuals who can afford to pay it on their own do not need a loan from the firm.

Due to their financial stake in the firm, equity partners have a greater stake in its success. Whenever the firm is financially successful, they are also financially successful.

Different law firms use the title partner differently. This depends on the person's position within the firm and the tier in which they are situated. Every kind of partner gets a similar set of benefits, including health insurance, pensions, and other amenities. However, there is no literal change from being a non-equity partner to an equity partner. The job title may sound similar, but the job responsibilities, benefits, and expectations are very different. Many AmLaw 200 firms have both non-equity and equity partners. Depending on your ambitions, your finances, and your goals, you will determine what kind of career you want to pursue.

Conclusions

Unlike associates, where the rules of compensation, advancement, and so forth appear very clear, it is far less so with partners.

- If an associate is a certain class year and bills a certain amount of hours then the associate can expect to make a certain amount of money—not so with partners.

- If the firm is doing well and the associate is busy, and not too senior, then the associate will keep his or her job—not so with partners.

- If the associate is in an active practice area and has good credentials, the associate can get another position without too much difficulty—not so with partners.

Though “making partner” is considered a huge badge of honor, partners in large American law firms also have to deal with an enormous amount of stress and contend with many significant difficulties daily. In fact, while many associates believe that they have a more difficult job as compared to the partners for whom they work, many partners have the opposite feeling. Given the pressures partners face each day, many feel that being a partner is far more difficult than being an associate.

About Harrison Barnes

No legal recruiter in the United States has placed more attorneys at top law firms across every practice area than Harrison Barnes. His unmatched expertise, industry connections, and proven placement strategies have made him the most influential legal career advisor for attorneys seeking success in Big Law, elite boutiques, mid-sized firms, small firms, firms in the largest and smallest markets, and in over 350 separate practice areas.

A Reach Unlike Any Other Legal Recruiter

Most legal recruiters focus only on placing attorneys in large markets or specific practice areas, but Harrison places attorneys at all levels, in all practice areas, and in all locations-from the most prestigious firms in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., to small and mid-sized firms in rural markets. Every week, he successfully places attorneys not only in high-demand practice areas like corporate and litigation but also in niche and less commonly recruited areas such as:

- Immigration Law

- Workers Compensation

- Insurance

- Family Law

- Trust and Estate

- Municipal law

- And many more...

This breadth of placements is unheard of in the legal recruiting industry and is a testament to his extraordinary ability to connect attorneys with the right firms, regardless of market size or practice area.

Proven Success at All Levels

With over 25 years of experience, Harrison has successfully placed attorneys at over 1,000 law firms, including:

- Top Am Law 100 firms such including Sullivan and Cromwell, and almost every AmLaw 100 and AmLaw 200 law firm.

- Elite boutique firms with specialized practices

- Mid-sized firms looking to expand their practice areas

- Growing firms in small and rural markets

He has also placed hundreds of law firm partners and has worked on firm and practice area mergers, helping law firms strategically grow their teams.

Unmatched Commitment to Attorney Success - The Story of BCG Attorney Search

Harrison Barnes is not just the most effective legal recruiter in the country, he is also the founder of BCG Attorney Search, a recruiting powerhouse that has helped thousands of attorneys transform their careers. His vision for BCG goes beyond just job placement; it is built on a mission to provide attorneys with opportunities they would never have access to otherwise. Unlike traditional recruiting firms, BCG Attorney Search operates as a career partner, not just a placement service. The firm's unparalleled resources, including a team of over 150 employees, enable it to offer customized job searches, direct outreach to firms, and market intelligence that no other legal recruiting service provides. Attorneys working with Harrison and BCG gain access to hidden opportunities, real-time insights on firm hiring trends, and guidance from a team that truly understands the legal market. You can read more about how BCG Attorney Search revolutionizes legal recruiting here: The Story of BCG Attorney Search and What We Do for You.

The Most Trusted Career Advisor for Attorneys

Harrison's legal career insights are the most widely followed in the profession.

- His articles on BCG Search alone are read by over 150,000 attorneys per month, making his guidance the most sought-after in the legal field. Read his latest insights here.

- He has conducted hundreds of hours of career development webinars, available here: Harrison Barnes Webinar Replays.

- His placement success is unmatched-see examples here: Harrison Barnes' Attorney Placements.

- He has created numerous comprehensive career development courses, including BigLaw Breakthrough, designed to help attorneys land positions at elite law firms.

Submit Your Resume to Work with Harrison Barnes

If you are serious about advancing your legal career and want access to the most sought-after law firm opportunities, Harrison Barnes is the most powerful recruiter to have on your side.

Submit your resume today to start working with him: Submit Resume Here

With an unmatched track record of success, a vast team of over 150 dedicated employees, and a reach into every market and practice area, Harrison Barnes is the recruiter who makes career transformations happen and has the talent and resources behind him to make this happen.

A Relentless Commitment to Attorney Success

Unlike most recruiters who work with only a narrow subset of attorneys, Harrison Barnes works with lawyers at all stages of their careers, from junior associates to senior partners, in every practice area imaginable. His placements are not limited to only those with "elite" credentials-he has helped thousands of attorneys, including those who thought it was impossible to move firms, find their next great opportunity.

Harrison's work is backed by a team of over 150 professionals who work around the clock to uncover hidden job opportunities at law firms across the country. His team:

- Finds and creates job openings that aren't publicly listed, giving attorneys access to exclusive opportunities.

- Works closely with candidates to ensure their resumes and applications stand out.

- Provides ongoing guidance and career coaching to help attorneys navigate interviews, negotiations, and transitions successfully.

This level of dedicated support is unmatched in the legal recruiting industry.

A Legal Recruiter Who Changes Lives

Harrison believes that every attorney-no matter their background, law school, or previous experience-has the potential to find success in the right law firm environment. Many attorneys come to him feeling stuck in their careers, underpaid, or unsure of their next steps. Through his unique ability to identify the right opportunities, he helps attorneys transform their careers in ways they never thought possible.

He has worked with:

- Attorneys making below-market salaries who went on to double or triple their earnings at new firms.

- Senior attorneys who believed they were "too experienced" to make a move and found better roles with firms eager for their expertise.

- Attorneys in small or remote markets who assumed they had no options-only to be placed at strong firms they never knew existed.

- Partners looking for a better platform or more autonomy who successfully transitioned to firms where they could grow their practice.

For attorneys who think their options are limited, Harrison Barnes has proven time and time again that opportunities exist-often in places they never expected.

Submit Your Resume Today - Start Your Career Transformation

If you want to explore new career opportunities, Harrison Barnes and BCG Attorney Search are your best resources. Whether you are looking for a BigLaw position, a boutique firm, or a move to a better work environment, Harrison's expertise will help you take control of your future.

Submit Your Resume Here to get started with Harrison Barnes today.

Harrison's reach, experience, and proven results make him the best legal recruiter in the industry. Don't settle for an average recruiter-work with the one who has changed the careers of thousands of attorneys and can do the same for you.

About BCG Attorney Search

BCG Attorney Search matches attorneys and law firms with unparalleled expertise and drive, while achieving results. Known globally for its success in locating and placing attorneys in law firms of all sizes, BCG Attorney Search has placed thousands of attorneys in law firms in thousands of different law firms around the country. Unlike other legal placement firms, BCG Attorney Search brings massive resources of over 150 employees to its placement efforts locating positions and opportunities its competitors simply cannot. Every legal recruiter at BCG Attorney Search is a former successful attorney who attended a top law school, worked in top law firms and brought massive drive and commitment to their work. BCG Attorney Search legal recruiters take your legal career seriously and understand attorneys. For more information, please visit www.BCGSearch.com.

Harrison Barnes does a weekly free webinar with live Q&A for attorneys and law students each Wednesday at 10:00 am PST. You can attend anonymously and ask questions about your career, this article, or any other legal career-related topics. You can sign up for the weekly webinar here: Register on Zoom

Harrison also does a weekly free webinar with live Q&A for law firms, companies, and others who hire attorneys each Wednesday at 10:00 am PST. You can sign up for the weekly webinar here: Register on Zoom

You can browse a list of past webinars here: Webinar Replays

You can also listen to Harrison Barnes Podcasts here: Attorney Career Advice Podcasts

You can also read Harrison Barnes' articles and books here: Harrison's Perspectives

Harrison Barnes is the legal profession's mentor and may be the only person in your legal career who will tell you why you are not reaching your full potential and what you really need to do to grow as an attorney--regardless of how much it hurts. If you prefer truth to stagnation, growth to comfort, and actionable ideas instead of fluffy concepts, you and Harrison will get along just fine. If, however, you want to stay where you are, talk about your past successes, and feel comfortable, Harrison is not for you.

Truly great mentors are like parents, doctors, therapists, spiritual figures, and others because in order to help you they need to expose you to pain and expose your weaknesses. But suppose you act on the advice and pain created by a mentor. In that case, you will become better: a better attorney, better employees, a better boss, know where you are going, and appreciate where you have been--you will hopefully also become a happier and better person. As you learn from Harrison, he hopes he will become your mentor.

To read more career and life advice articles visit Harrison's personal blog.