The Dangers of Chasing Status

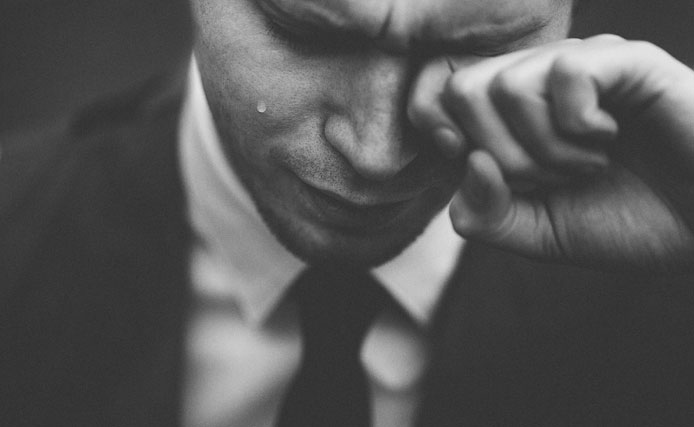

Two of my high school friends have died recently. One, an attorney, died when he committed suicide after getting disbarred for embezzling money from a client. Richard had been chasing success for years. He had worked at a series of law firms in Miami and a few other large cities after graduating from law school. He always wanted to be rich, successful and be someone important. At one of the last high school reunions, he had gone around telling everyone that he had developed some sort of app and sold it for hundreds of millions of dollars. This was not true, of course, but he wanted to be seen as someone very rich and important. His identity and the way he wanted to be seen in the world were about his ability to get things that most people want. He was trapped in an endless cycle of chasing status, trying to look good to others and trying to feel good about himself.

Richard’s mother was from a wealthy family in Michigan—her father was a well-known, successful attorney—and she had moved down to Florida, become a drug addict and had a series of difficulties that ended with her giving Richard to his grandparents. Richard’s wealthy grandparents sent him to the boarding school I attended. Here, he was surrounded by many high achievers. I was friends with Richard until he showed up outside one of my classes in 10th grade and asked me if I wanted to skip class and go snort cocaine with him. Before that time, Richard had an unnatural interest in girls and was jumping out of his dorm window almost nightly chasing an endless variety of girls—whom I had no idea how he met.

I was a wild kid and by then was drinking beers nearly every weekend, but I decided he was on a path I was not interested in being on. Despite this, Richard was a decent student and always very motivated. He wanted to do well in school, wanted to be successful and wanted cars, houses, a family and the things we are all supposed to want. He was surrounded by others who wanted these things as well.

I had referred Richard to a site our company runs, LawCrossing, years ago and he was extremely grateful and had written me a glowing recommendation that I subsequently lost. When I looked for the recommendation, I could not find it. The only thing I could find was an announcement online that he had been disbarred. When I searched for his contact information on the State Bar website, it said he was deceased. I ended up finding an announcement that he had died the day after being disbarred. I found a small announcement about his death on a Detroit funeral home website. When I asked several of his high school friends about his death, to my astonishment no one knew he had died. The family had kept it secret from everyone. This made me very sad because he had died without anyone knowing.

Have you seen this happen to an attorney that you know? Share what happened in the comments below.

Please see the following articles for more information:

- Another Lawyer Suicide: How the Psychology of Being a Big Firm Lawyer Can Tear You Down

- Why Do So Many Attorneys Ask "What's the Point?"

- Another Big Law Attorney I Know Just Died Young

- Seven Reasons Why Practicing Law Might Be More Stressful than Spending 18 Months in a POW Camp

Throughout the years Richard contacted me now and then to see how I was doing. Everything he would say was always related to money, status, where people were living, what jobs he had and so forth. It seemed the only thing that interested him was talking about these things—and “one-upping” anyone who spoke about them.

What killed Richard was the same thing that kills and has resulted in many attorneys I know having horrible lives: Richard was constantly chasing shiny objects. Richard wanted success and possibly felt that success would someone fill a void he had inside of him. Perhaps that void was related to the problems Richard had growing up. Or, the void may have been related to trying to prove something to his high school classmates, other attorneys, his grandparents—I do not know. Whatever the void was, Richard wanted to be someone different than he was and spent his entire career and life chasing this. He did not give up until being disbarred. Being disbarred is serious, and I am sure it would have altered his life immeasurably. But being disbarred is not a prison sentence, and it does not mean you have to die. Practicing law is not that important—many attorneys kill themselves because they have to practice law and not because they are ordered not to do so.

If you kill yourself when you realize that you no longer can practice your profession, it shows just how much your identity and life is wrapped up in how others see you and these sorts of outward signs of success. Is being a lawyer that important? Was access to the $15,000 Richard stole so important that he needed to risk his career for it. Was chasing the best job he could in a law firm after law firm worth it for Richard? I do not know. Most attorneys and others are chasing success and keep doing so throughout their career.

Attorneys in large, competitive cities and large competitive firms are, as a general rule, unhappier and less content than their counterparts in smaller cities and smaller firms. If a survey was done, I believe it would conclude that these attorneys also die earlier than their counterparts in smaller cities and smaller law firms around the country.

How do you feel about the practice of law? Share your feelings below.

Please see the following articles for more information:

Why the Most Successful Attorneys Are Often the Unhappiest

It seems that attorneys who are the most highly credentialed, doing the most sophisticated work and making the most money are the unhappiest practicing law. Conversely, the attorneys who are the least credentialed, working in the smallest cities and firms often may not feel the best about their compensation but might be the happiest.

Why do the smartest attorneys often find themselves the unhappiest?

When you look at our careers and lives, the choices are fairly simple because we all are in control of our lives. We can live where we want, work where we want and associate with those we want. Our freedom to choose is unlimited. We can choose to rent or buy, marry or not marry, save or not save, travel or not travel. The myriad of choices we have is remarkable and unlimited. You would think that having the ability to make so many choices that we would make choices that would make us the happiest – especially the smartest people.

Despite this fact, we often make decisions that are at odds with our happiness.

One decision we might make that hurts us is to buy a car, house, or something else that costs far more than we can afford—or is at the limits of what we can afford. Law firms, for example, traditionally love it when their attorneys buy expensive homes, have children, support a stay at home spouse, enroll their children in expensive private schools and make similar choices. The reason they like these choices is that once an attorney chooses this, they are figuratively building their prison and making the law firm their master. A home that is more than the attorney can afford means the attorney does not want to risk losing their job (and their home). Children, stay at home spouses, and expensive schools are similar things that serve to box the attorney in.

In large cities, attorneys will want to live in the best neighborhoods, drive the best cars, send their children to the best schools and do what they can to have strong, externally focused realities that look good to the outside world. An attorney often cannot possibly afford to lose their position with a major law firm if they have these sorts of expenses and are depending on the law firm. The law firm, therefore, will be able to demand more and more hours, more and more business and the attorney will be imprisoned to this reality.

Attorneys imprison themselves with their financial choices. These choices often give them no option but to work in the largest cities, in the largest law firms, working the most hours, having the most unpleasant commutes and the law firm as their jailer.

Choosing to indebt yourself to others has other drawbacks than being bound to the work as well: Many of the most successful male and female law firm attorneys I know that are married have been divorced—and consistently get divorced. They can attract and woo wonderful mates and provide well for them financially – but they are never there to spend quality time with their spouses. If you are never there to nourish a marriage, the other partner gets lonely. When you are there you may be exhausted and unable to connect emotionally. Without any sort of support, the neglected partner becomes interested in leaving after some time – even though their financial needs are met. Many attorneys in the largest law firms are showing up to work but not showing up to life.

The attorneys who I work with and have been for years are often quite dissatisfied with their work—but not all are. Practicing law can be very enjoyable for some attorneys; however, it is not for all attorneys.

Why do the best attorneys get caught in this cycle of work for work's sake? Is it only servicing debt, or is it something else?

Attorneys in the largest cities are guilty of what I call “chasing shiny objects syndrome.” They are constantly chasing something better, or different in their legal careers. They often believe that the grass will be greener somewhere else and that this will make them happier and better.

Attorneys start chasing shiny objects the moment they start applying to law schools. The first shiny object is the law school. They want to get into the best law school possible. Many (if not most) attorneys enroll in law school with little idea of what it is like working in a law firm, or what they will even be doing once they get there. Poets, mathematicians, musicians, scientists, and others enroll with no more than a half-witted understanding of what they are getting into. Whatever their former passion was before going to law school, which is generally left behind.

|

|

If they do not get into the best law school, these attorneys will often make a serious effort to try and transfer after their first year. If that does not work out, they often go and get an LLM later on from a more prestigious law school to get that on their resume.

Attorneys start chasing grades and other honors once they arrive in law school. Then they chase the best summer jobs they can get—and after a few years a whole class system has developed, and the attorney knows exactly where they fit. Because somewhere else is often better than where they are (a great many attorneys are unhappy), the most motivated will often try and move a few times to a better firm, one that has a different culture, one that is in a different part of the country, or a firm that does a certain type of work. The attorney will then “buckle down” and try and make partner in a firm. If they do not make partner at their current firm, most attorneys will move to a firm that will make them a partner. Of course, many firms may make them a nonequity partner instead of an equity partner—and the race for titles, honors and so forth will simply continue.

After making partner, the partner will try and get more business and may try and move to a better firm again once they get a certain sized book or certain types of clients. Partners compete to get the most points and the best compensation in their current firms and in the new ones they join as well. The idea is that these moves and the ability to get into progressively better firms will somehow make the attorney whole and better: Attorneys, like most of us, want to believe the grass is greener somewhere else.

The classic “grass is greener” move that attorneys make is seeking in-house positions. This career move is full of more danger than almost every attorney realizes—but it can work out. An attorney seeking in-house positions believes that these positions will free them from the pressure of practicing law and finally make them happier. In-house, though, can be even crazier than working in a law firm. Suddenly an in-house attorney finds themselves a “cost center” whose relevance and survival depends on whether the current General Counsel or CEO likes them, the performance of the company’s products and services in the market and whether the attorney knows how to play corporate politics. In-house jobs rarely end well—but they can work. In most instances, an attorney will not last in any in-house position more than a few years, will take a huge hit in compensation and will also be likely to have serious issues getting a new job when they lose their existing one (because most in-house attorneys do).

Have you had a similar experience? What ended up happening? Share your experience in the comments!

See the following articles for more information:

- Going In-house? Why You May Be Saying Goodbye to Law Firms for Good

- What Do In-House Attorney Positions Pay?

There is, of course, nothing wrong with self-improvement or trying to better oneself. This is human nature and healthy in many respects. However, the problem with a great many attorneys is that they are unhappy because they are completely misaligned. They are (1) imprisoned financially and (2) addicted to chasing shiny objects. Attorneys learn to chase shiny objects early in their careers, and they never stop. Once imprisoned financially, an attorney chasing shiny objects never really stops doing so unless they make the incredibly evolved decision to realize (1) they are imprisoned through their own self-will and (2) their addiction to money, status and something else is driving their unhappiness.

My other friend, Daniel, died from drug-related issues after spending his life aimlessly doing not much of anything—using drugs heavily, drinking and otherwise feeling sorry for himself. Daniel came from a family of high achievers. His family had owned a large construction company in Michigan, and he had two brothers—both of who became quite successful. Daniel was a fun person to spend time with in high school, but he drank a great deal, used drugs and was motivated more by meeting girls and abusing substances than doing well in school, or becoming anything.

Is your job right now making you happy? Share your answer in the comments below.

Here are some resources about attorney stress and ways to help you handle it:

- Attorneys Have Problems with Drinking

- Survival Tips for a First-Year Associate

- Understanding Stress and Attorney Relations

- Attorneys, Life Events and Stress: Causes and Palliatives

- Lawyer Stress

- Talk Straight if You Want to Handle Stress in Law Firm Offices

- Ways to Cope with Stress in a Legal Career

- Ways to Effectively Manage Stress

The Hidden Cost of Competition

Early on I think that Daniel realized that he did not have the drive, or intelligence, to do as well in school as the majority of people he was surrounded by. He was also not a particularly good athlete, or good at anything for that matter. Unable to compete at the level of the people he was surrounded by, he quit and dropped out rather than doing the best with what he was given. He was surrounded by kids at our school who for the most part went to top colleges and became very successful. I am sure Daniel could have done very well too if he had given himself a chance and competed at a level that made sense for him, but he gave up.

Because Daniel was surrounded by so many kids who ended up going to Ivy League schools and doing so well, he never received positive feedback from his teachers or environment. All he saw around him was wealth and people doing better than him—his brothers, his father, his friends. This did not make him feel good about himself, and he ended up becoming a joker and numbed his sense of inadequacy with substances. The fact is that Daniel was someone very talented and likable with many skills. Nevertheless, because he was surrounded by so many people who gave him negative feedback, he never was able to get positive reinforcement or feel good about himself. To develop an identity that made sense for him, in his junior year, he started following the Grateful Dead, grew his hair long, grew facial hair and started wearing tie-dye clothes and dressing and acting like a hippie.

Daniel reminds me a lot of attorneys I see who go to the most competitive law firms, and who, for whatever reason, should not be there. The most competitive law firms require a drive to work very, very hard. These law firms also demand that you be very smart, not make errors and want to succeed. The sort of people who work there are extremely competitive with one another and masters of undermining each other. Every year I see attorneys who land in these firms—or who have been working there for some time—and have their spirits crushed. They simply do not have the drive, or fortitude, to survive in these environments and many attach their self-worth to working in these sorts of firms.

When you are in competitive environments that make no sense for you, there are typically a few choices that you face: One, you can try and pick up your game and compete; two, you can compete in a less competitive arena; or, three, you can drop out completely.

Daniel chose three—he dropped out completely. He started following the Grateful Dead and doing other things that gave him an excuse not to compete. Later in Daniel’s life, he stopped doing much at all and moved through a series of colleges, jobs and geographic locations for most of his life.

Many attorneys end up giving up completely when surrounded by other attorneys who are incredibly competitive. Early in their careers, they lose the motivation to make the most of themselves because they feel that keeping going is too difficult. Many attorneys exposed to incredibly competitive law firms quit the practice of law entirely. A great many of these attorneys quit law firms because they find them too competitive and difficult.

I often observe that if these same attorneys had gone to smaller law firms, or worked in smaller cities, they would have had much more rewarding (and happy) careers. Instead, they believe that if they cannot compete at the highest level possible, they should give up.

Daniel might still be alive, have a family and have had a good career if he had, instead, not felt so demoralized by his inability to compete with his peers and done his best, or gone to public and not a private school. Like many attorneys not suited to the environments they are in, Daniel could have been much happier if he had allowed himself to be surrounded by more supportive peers.

By the time Daniel was in his mid-20s, people that he had known in high school had zoomed past him with career and lives that Daniel never had. Daniel never married, and when he died, he was living with his brother and his family in Florida. The last time I saw Daniel he was disheveled, had grown a beard and did not look that healthy. He was “off” and did not seem that together.

These two individuals stick out for me because both were surrounded by people chasing success—one tried to chase success and failed, and the other gave up chasing success. One killed himself because he wanted success too much and cut corners and could not see himself functioning in life without a law degree. The other I believe slowly killed himself while drowning his sorrows and sense of lack from an inability to compete with drugs and alcohol: He never could be the person his parents, brothers, and others could be.

Was it worth it for Richard to have spent his life chasing something only to kill himself when he realized all his work was meaningless? Was it worth it for Daniel to have given up chasing success when he could have achieved something had he not given up? Did Daniel spend his life using substances and drowning his sorrows because he could not stop comparing himself to others and feeling like he did not measure up?

How Attorneys Trap Themselves in Unhappiness and Financial Obligation

About fifteen years ago, I purchased a 9,000 square foot house surrounded by nine-foot walls, on a giant lot with a koi pond, huge saltwater aquarium “viewing room”, impressive water features surrounding the property, a tennis court, Olympic sized pool, massive garage, and murals painted on the ceilings by Italian painters one of the previous owners had brought in. For years I had driven by the home and always wondered who would live in something so remarkable. Now I was living there. It was just my new wife and me. There was absolutely no reason I should have been living in such a house, and it was a complete waste on so many levels—financially and otherwise.

On the day that I moved into the home, I remember going and sitting by the monstrous pool on a lawn chair and suddenly feeling incredibly depressed. I did not know then why I was depressed. What I now realize was that I had purchased something because I thought it would make me happier, or take me closer to something that I needed and it could not. I realized I had been working all these years furiously—in college, law school, in law firms and my businesses—and that for me all of this work and sacrifice had presumably been done in search of shiny objects like this. I realized the home meant close to nothing but that I had purchased it because I needed to have some reassurance that all I had worked for had been for something like this.

In pursuit of this success, I had imprisoned myself with a huge mortgage, property tax payments and more because I had something to prove—whether it was to myself or others. In the previous few years, I had purchased buildings, warehouses and other things that I did not need that also boxed me in but made me feel successful. While I was not overextending myself at the time, the financial crisis had not happened yet—and it would—and when that happened things would not go well. However, before the financial crisis hit, I would sell that house to a famous producer, Gail Hurd, and purchase an even more impressive house in Malibu, California right next to Brad Pitt—something I also did not need.

Earlier in my life, I had worked extremely hard in college so I could get into a good law school. Then I had worked incredibly hard in law school so that I could get into a good law firm. Then I had worked incredibly had in a law firm so that I could become a partner. Then I had realized that I was putting all of my life energy and motivation into something that was a risky proposition and that I should put it in a better field where I had more control over my compensation—and I started a business. When I started the business, I wanted it to be the best and put all of my energy into this.

Our energy goes towards things that make us stronger and those around us stronger. We try and succeed and do the best we can and achieve as much as we can until we get tired, retire and eventually die. The entire cycle is based on trying to be as much as you can as fast as you can while you have the energy to do so.

What are some ways you have found to channel your energy in a positive way?

Please see the following articles for more information:

- Two Fatal Deficiencies That Prevent 99% of Attorneys from Achieving Greatness

- The Similarities between Human Trafficking and Practicing Law: Why Control and Energy Are So Important to Your Life and Career

Most attorneys—more so than many others—are caught up in a game of chasing shiny objects: They are interested in what they currently do not have but would like to have. It is our fascination with shiny objects that allows us to be exploited and taken advantage of both by our employers and society at large. It is this fascination with shiny objects that creates out unhappiness.

What we do not have can take a variety of forms. It could be material such as a home, a better home, a car, a better car. It can be titles. It can be money in the bank.

Attorneys are unhappy for several reasons. It is not unusual for others to have financial obligations—everyone does. The problem with the practice of law, though, is that a substantial portion of attorneys do not enjoy it. Despite not enjoying it, they are constantly motivated to change and try something else in the profession that will make them happier, or more fulfilled. It rarely does. Most partners I speak with have issues with their firms they are unhappy with – most associates do as well. These attorneys are unhappy not only with the system of practicing law but often the work itself.

Envy and financial obligations are the Achilles Heel for many of these attorneys that keep them going in the face of a profession they are unhappy in. If you are truly unhappy doing something, the most logical thing you can do is leave it. If your debts and obligations are keeping you from doing what you want, the most logical thing you can do is to not get into any more obligations and get out from those that are keeping you enslaved. If your work is making you unhappy, you need to stop doing what you do not enjoy and do something you are passionate about that makes you happy. If the people you are working with do not make you happy, you need to work with those who do make you happy.

The further danger in chasing shiny objects is that when you do this, you are never committing to where you are at right now. Instead, you are always seeking something different. Your goals are misaligned with your actions. How can you possibly be doing a good job in your existing position if you are interested in doing something else entirely?

You can never be happy when you have comparison syndrome. Comparison syndrome means you base your self-worth on what others around you are doing and achieving. It is ignorance that keeps you bound to whatever you are doing.

If you do not enjoy practicing law, you are either (1) chasing shiny objects and imprisoned by that, or (2) in a cycle of envy that does not allow you to let go. The only solution to any of this is the most obvious: You need to open the door and walk out of prison. You need to work with people you like and live in a way that you can afford that makes sense.

Have you ever made a bad decision based on what seemed most profitable at the time? If so, what did you learn from it? Share your experience below.

See the following articles for more information:

- Why You Should Find Your “Tribe” and Not Just Focus on Money in Making Law Firm Job Decisions

- Love What You Do

- You Need to Enjoy What You Are Doing

- Never Focus on the Money: Focus on Your Higher Purpose and Contribution

My friend Richard had problems in his life and died because he was overcome with envy and chasing shiny objects. My friend Daniel died because he felt he could not compete with the people around him and dropped out of life completely. In truth, Richard was a good attorney and could have been happy if he was not so enthralled with money and success. Daniel could have had a good life and career if he was not so beaten down by his inability to compete at a high level. It is enough just to compete and be. We do not need to be the most successful, but we also should never quit.

Conclusion

One of the most important pieces of advice anyone can ever give you is to not worry about others and not attach your self-worth to what others are doing. That sort of thinking imprisons you and makes it impossible for you ever to be happy. Comparison syndrome will either crush you or drive you to great levels of unhappiness chasing something that does not matter. You should never give up. That is the dumbest thing you can do. You should also not worry about others—surround yourself with people who value you and not those who are making you neurotic and crazy. I’ve seen far too many attorneys give up and others die slow, tortured deaths in law firms when they are driven by money and envy. This is the source of your problem, and you need to realize this before you can be happy.

How do you feel about the practice of law? Share your feelings below.

See the following articles for more information:

- 25 Reasons Most Attorneys Hate the Practice of Law and Go Crazy (and What to Do About it)

- Ways to Cope with Stress in a Legal Career

- Ways to Effectively Manage Stress